In September 1942 I walked boldly up the steps for my first kindergarten day at Franklin Grove School. The classroom looked huge. From his portrait on the wall, George Washington’s watchful eyes followed my every move.

Our farm was almost two miles away, a 30-minute walk for me and my sister Carolyn, who was starting third grade. If the dirt roads were muddy, the sticky clay loam built up on our 4-buckle overshoes and we needed almost an hour—arriving four pounds heavier and two inches taller.

I already knew all 20 kids from our neighborhood in Pierce Township, Page County in Southwest Iowa. And I’d closely followed Carolyn’s highly enthusiastic first three years at Franklin Grove. I knew I could count on her protection. And on her uncanny ability to relay my school misdemeanors to Mom and Dad.

My three kindergarten classmates—Pat Drake, Joyce Royer and Dwight Iverson—were already friends, and remain friends today, after 80 years.

World War II was exploding in Europe and the Pacific, but seemed far away.

I delighted in my kindergarten and first grade teacher, Arlette Kampe, the most lovely and gracious young woman I’d ever seen. She—and her father—were graduates of Franklin Grove. In my final kindergarten report card, she wrote: “Jerry is a good reader. I hope he will always keep this up because if he can read well, he will be a far superior student.”

Franklin Grove School had no running water. No phone. A huge cast-iron stove fired with corncobs and coal heated the room.

Two outdoor toilets—a boys’ and a girls’—stood near the northwest and northeast corner of our one-acre schoolyard. “Gender dysphoria” had not yet been invented by corporate pharma. Preferred pronouns were only for English class.

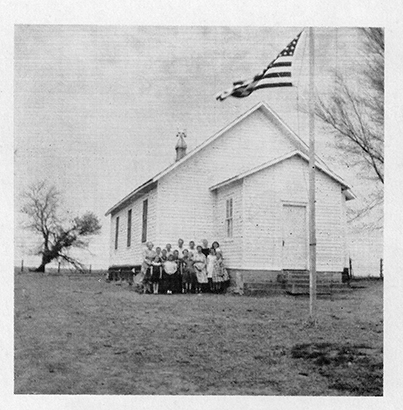

Every morning in fair weather, kids gathered around the flagpole while a student took his or her turn raising the American flag. Right hands over our hearts, we recited in unison, “I pledge allegiance to the flag of the United States of America and to the Republic for which it stands, one nation under God, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all.”

Every kid brought a lunch from home. I preferred to carry it in a paper bag, which could be folded and returned home in a pocket. Sometimes Mom insisted on a lunch bucket which could hold a Thermos jug of hot soup. On most days, kids scattered around the schoolyard to eat their sandwiches and apples on the soft grass or under the shade trees. Over lunch, we learned a lot about negotiating deals. The most valued trade item was a weenie sandwich. In winter we’d split the hot dog lengthwise and sizzle it on the ceramic-coated top grill of the big stove, while toasting the bread.

(Later at Essex High School in 1955, “hot lunch” was a highly overrated perk featuring acres of lasagna made with surplus USDA commodities. I often brought a healthy lunch from home.)

Our teachers required every student to wash hands before lunch at the sink in a rear corner. Each kid filled his own tin cup with water from the 7-gallon Red Wing ceramic crock, and used that water to wash. Everyone also brought a personal towel to dry. With the sink plug pulled, soapy water drained out a pipe through the side of the school, irrigating a lush patch of grass. The Page County Public Health Department never found occasion to visit.

Every morning recess, two big kids—boys or girls fifth grade and up—walked about 600 yards downhill across a cow pasture to Riley McClintock’s outdoor well pump, and filled a 4-gallon pail with a tight lid. Rain, snow or shine, this water supply was essential. In my seven school years there, I never saw a boy ducking water duty. In winter, that steep hill was an exciting Flexible Flyer sled run, which also made pulling 32 pounds of water easy back uphill.

Every student had a job. Examples: Carrying in cobs and coal from the “coal house” nearby. Dusting erasers outside. Washing the 24-foot-long slate blackboard. Sweeping the floor with sweeping compound. Filling the kindling basket with wastepaper to light tomorrow’s fire. Seventh and eighth grade students tutored younger kids in spelling and math. If big kids hadn’t gotten the lesson in the first five grades, teaching it locked it in memory.

In my fourth grade, Dad bought a gentle bay mare, Princess. Carolyn, three years older, always rode in the saddle. I perched behind. Carolyn warned: “If you sit the saddle and hold the reins, Princess will gallop like crazy.” Which is exactly what I had in mind.

On the way home, Carolyn couldn’t hold back Princess anyway. During the day, Princess grazed the grass in reach of her 10-foot tether. One of my after-school chores was scooping up the biscuits Princess deposited. I tossed droppings over the fence, fertilizing Frank Galinghorst’s cornfield.

About once a month on a Friday after school, the “Missionary Lady” visited. Most kids stayed for a half-hour multimedia show: A Bible story unfolding across eight feet of “flannel-graph” panels. We gasped at the dramatic defeat of Goliath. Visualized weeds and thorns suffocating a believer’s faith. Learned how a father could love and forgive a prodigal but repentant son.

The School Board approved these after-school religious visits. Traditionally in the late 1800s, the schoolhouse had doubled as a center of community social life, including Sunday worship services. During that era, Pierce Township dedicated a cemetery which cornered on the schoolyard. It was a “dare you” challenge after school to explore the sunken graves and mossy gravestones of our neighborhood ancestors. Often we’d find human bones which groundhogs had excavated. I found a jawbone once, but freaked out, tossed it down the groundhog hole and covered it.

The board couldn’t find a teacher for our 1947-48 school year, my fifth grade. Carolyn and I were sent to a Montgomery County “consolidated” school at Coburg, a village of less than 100 people. This required a grueling 45-minute bus ride before and after school, plus a quarter-mile walk across the Montgomery County line to the school bus stop. On bitter cold days, a neighbor, John Chandler, let Carolyn and me wait inside his porch until the bus arrived. Coburg had elementary and high school students packed in one building.

Carolyn was in eighth grade—vivacious, attractive and athletic. She was a star basketball player, and decided to attend Coburg for her high school years. She thrived, and during the following four years often brought home up to four gorgeous girlfriends for overnights at our house. Their “pajama parties” accelerated my adolescence.

But my fifth grade at Coburg suffered academically. I learned about high school bullies, pornographic comic books an an astonishing array of cuss words.

In 1947, electricity finally arrived in Pierce Township, thanks to the Rural Electrification Administration (REA). My Dad, Glenn Carlson, wired the Franklin Grove classroom with six bare overhead light bulbs. That opened opportunities for special evening programs for parents, such as spelldowns where Pat almost always beat me in front of every kid and their parents.

For the 1947-48 school year, Dad spurred the Franklin Grove school board to hire an excellent teacher, Dorothy Journey. Dad and Mom heartily supported our country school. Dad had graduated from Franklin Grove in 1922, and later served as School Board secretary for a quarter-century.

My sixth, seventh and eighth school years restored my academic enthusiasm, which had slumped at Coburg.

I also gained new transportation: Dad and I built my 40-mph “Blue Racer,” a 10-foot streamlined race car with 12-inch tires, a 7.5-hp Wisconsin engine and motorcycle transmission. New commuting time: 3.5 minutes, except for the day I T-boned one of Frank Gallinghorst’s 180-pound hogs. Whichever way I zigged, the hog zagged in front of me. On impact with my left front tire, the hog spun like a top into the ditch. The hog limped away, but my left front wheel wrapped 90 degrees, demolishing my steering gear.

In 1948-49, our student body entered a county contest to promote soil and water conservation by creating a thick 8.5- by 11-inch notebook visualizing our parents’ terraces, waterways and contour farming. Title was the acronym SOIL: Save Our Iowa Land. We won. Today, the rolling hills of Page County are mostly terraced and waterways protected.

Franklin Grove graduates typically earned higher grades than “town kids” at Essex High School, which stressed academic excellence along with a conference-winning football team. With a student body of about 100, Essex High fielded an 11-man team. I played fullback, eager to crash into live bodies.

At Iowa State, I realized what a strong foundation Franklin Grove teachers had built under my ability to learn. I immediately upgraded to advanced English. Earned several academic honors and eventually an MS degree in journalism. My master’s thesis: How future journalists would write on computers and transmit news instantly. I became Managing Editor of Farm Journal, later co-founded Professional Farmers of America, and in 2008 launched our family firm, Renewable Farming, now owned by our son Erik and his wife Jeanene.

Now at age 86, I read daily reports of how parents are searching for ways to rescue their kids from costly classrooms in large schools burdened with: Covid mandates for masks and mRNA shots. Fentanyl and other drugs. Critical race theory and gender indoctrination. Pornography on school bookshelves. And sometimes, indifferent unionized teachers.

Today the fastest-growing kind of elementary education in America is home schooling, including neighborhood co-op schools. In 2022, about 12% of American households are home-schooling one or more children. That percentage doubled during the 1920-21 Covid craze. This fall, roughly 4 million elementary and high school kids are home-schooled. That includes our grandson, whom my wife Jill and I can hardly keep up with academically.

Just perhaps… many of our country’s parents are searching for a way back to a modern version of Franklin Grove for their kids.